Life on Abram Lake

Life as a rural physician Mama in the backwoods of Northwestern Ontario

The Medicine

Writer’s note: the patients in this piece are composites of multiple patient encounters to preserve patient confidentiality.

CTAS 3. Suicidal ideation, possible toxic Advil ingestion. Hallway chairs.

The metal clipboard clatters onto the desk as I flop into the worn chair in the doctor’s ER charting room. It pitches me forward at an awkward angle as I hammer my password for the millionth time that shift into the desktop login screen. Workplace ergonomics clearly hasn’t been a priority for the many weary bums who have briefly rested here before me. Little red ambulance icons fill the screen as I load the patient’s electronic chart revealing previous ER visits for similar presentations.

Through the glass, I glance at the nurses’ station where a comically small black bin provides a landing place for ER charts of patients waiting to be seen by me, the solo MD in our busy department at the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre. It’s an impossible dance, trying to keep pace with the growing pile. Ambulances pulling into the bay unloading medivacs from the North – patients already triaged to be the sickest of the sick, paramedics wheeling in gurneys of people picked up within town limits and of course, the seemingly neverending stream of walk-in patients presenting to triage.

Today is a shit day.

It’s a shit day because it is only an hour into my shift and already that ridiculous little bin has been shifted perpendicular to its usual position to make room for the endless stream of new ER registrants’ charts. Shortness of breath, weakness, abdominal pain, alcohol intoxication, back pain, ‘weak and dizzy’ – an endless barrage of chief complaints. Charts on top of charts, piling up, flowing from the confines of the inbox, snaking across the filing cabinet and now haphazardly falling to the floor.

A sideways chart day is never a good day.

Sighing, I make my way to the chair in the hallway that seats my next patient. Mental health assessments are never quick and I settle in beside her pulling my favourite pen from its usual spot lodged into the base of my ponytail. I long for a quick UTI, a prescription refill or a rash, something to help me catch up, but alas, this is not the case.

Lab techs whiz by us, coaxing white carts with clattering phlebotomy supplies through the maze of patients and IV poles clogging the hallway. Someone pounds insistently from the waiting room on the locked ER doors. The phone rings desperately as the clerk speaks rapidly on the other line. It’s not even close to an ideal place to inquire about one’s ugliest truths, but it’s all I’ve got. At least I’ve found two chairs.

My patient’s heavily-pierced face folds into a bright smile as I sit, her thickly-lined eyes disappearing into her grin. Her bright, outlandish outfit contrasts the bland grey and white hues of the department. We know each other well. A ‘friendly face’, as we call patients who come through our ER more regularly than some of our staff.

Today, she’s not interested in chatting. She grabs my hand and immediately pulls me into a hug.

Now, if you are in medicine, the thought of sitting in the ER hallway, letting a potentially unstable mental health patient hug you may be beyond unimaginable. I hear you. But as I sit there in her embrace, the comings and goings of the noisy ER flowing around us, more charts most definitely piling higher in that damn little box, I think of how little my medical ‘practice’ has to do with the actual practice of Western medicine. I relax my body and wait.

Minutes later she lets go, smiling her crinkly smile. We chitchat about her day and she tells me about her latest happenings since we last saw each other. I share an earbud and listen to the loop of her new favourite Top 40 hit as Justin Beiber struts across the screen of her beat-up iPhone. As I scrounge around the ER for a juice box and sandwich and in exchange, she agrees to my request for bloodwork and cardiac monitoring. Later, after Poison Control has been contacted and she’s medically cleared, she hands me a drawing she’s completed: a thank you note, brandishing a multitude of bright red hearts coloured in scented markers.

I step gingerly past the pile of ER charts still waiting for my attention and tape her drawing squarely onto the glass separating the doctors’ room and the chaotic nurses’ desk. Toxicology and acid-base physiology be damned, this is the medicine that matters. This is the medicine that fuels me. This is the medicine that I know I’ll die practicing.

After a year away from the Sioux Lookout Meno Ya Win Health Centre, nothing has changed, yet everything has changed. Post-COVID, human resource shortages are crippling across sectors without reservation, but health care has taken a weighty hit. At baseline, recruitment and retention of healthcare providers in our remote region have always been challenging. Complex patients, a high rurality index, virtually zero affordable housing and an exorbitant cost of living have always been colossal barriers. With a national nursing crisis, the situation in our little community has recently become dire.

Our small hospital, once staffed by local nurses who had spent their careers taking care of our patients has now been filled with nearly all agency nurses – temporary staff providing a warm body, filling an empty line in the schedule for a few quick months. Turnover is high, with nurses coming and going, mostly dropping in from the GTA to make a large amount of cash in a short period of time. Doctors being flown in from Toronto or other urban centres to cover a single ER shift all in an effort to keep the hospital doors open. Our Maternity nurses, once an integral part of our tight-knit program, colleagues on whom you relied on through tough cases are essentially all but gone, again replaced by temporary, agency nurses.

To these adventurous agency nurses, I am incredibly grateful. Most have proven to be fantastic – quick to learn, bringing knowledge and expertise from larger centres. Yet, without prior knowledge or understanding of our Region, the historical perspective of Indigenous peoples in this country, and knowledge of the intergenerational trauma and socioeconomic factors that continue to play a significant role in one’s ability to be well, it is difficult to truly provide medical care. Yes, of course, IVs continue to be started, medications administered, vitals taken, and physician orders executed, but in a sense, without trauma-informed, culturally-safe care, it all just seems so meaningless.

As threats of ER closures continue and human resource staffing plummets to an all-time low, not a day goes by where I don’t witness further erosion of empathy and care in the bare-bones operation of healthcare in our current political and economic climate. Nurses, doctors, clerks, housekeeping staff, lab techs – all of the folks that keep the cog turning are scraping from the bottom of the barrel to remain afloat and I’m terrified to see what will come next.

In our ER, I love being the 2-10pm guy. It’s the busiest shift by far but it allows me to see the kids in the morning and still sleep in my own bed at night. Today, as I lock my bike outside the ER entrance, saying farewell to the bright, sunny cloudless summer day, I already know it’s going to be a crazy shift. Two cop cars are parked out front, the ambulance bay is full and a flight from one of the larger communities must have just landed as all at once, at least ten patients are waiting to be triaged. Luggage bags and Tim Hortons take-out trays litter the floor of the waiting room. Balancing my coffee mug, I swipe myself into the ER, stepping carefully over a patient snoozing on the floor, sunglasses covering his eyes, his back slumped against the wall.

The trickiest part of the 2-10pm shift is dealing with the higher volumes of patients without any physical rooms to see people in. With no available beds on the inpatient wards, the steady influx of newly admitted patients clog up the ER all the while patients just keep on coming. Because of this, one of the first things I do at every shift is to take stock of where patients are, which patients could possibly be moved and where I could possibly squeeze someone new in.

Today, as I run through the ER whiteboard with my morning MD colleague, we realize that there is a patient who had been handed over from the overnight physician and had yet to be reassessed. Unfortunately, this happens all too often. Errors in care occur most commonly for patients who change hands from physician to physician during their stay in the ER department. People simply get lost in the shuffle.

Anxious to potentially free up this patient’s bed, I grab his chart and make my way down the hall and into a windowless room around the corner, away from the hustle and bustle of the nursing desk. A middle-aged man rests quietly on the gurney – no iPhone, no TV, no magazine or book to provide a mental escape from the incessant waiting. A quick glance around reveals no family member or friend accompanying him. The ER chart indicates he is from Poplar Hill, a fly-in Anishinaabe community of 500 people, some 300 kilometres north of Sioux Lookout. Sent to the ER by the community physician for an abdominal ultrasound, he had been triaged the evening prior, assessed by the overnight physician then held in the department for a morning ultrasound. Often patients are asked not to eat or drink prior to this type of investigation to allow for optimal views but in the morning change of guard, his ultrasound hadn’t been ordered, his chart was missed and thus he had been waiting patiently without anything to eat or drink for now over 14 hours.

“But his legs aren’t broken,” responds the nurse when I ask how this gentleman had been so grossly overlooked. “He could have come up to the desk and asked for food!” she says matter-of-factly. I know she’s not being unkind. From a large hospital in Southern Ontario, she’s at the end of her career and she’s truly seen it all. Efficient and with a no-nonsense attitude, she runs our department with a decisive air.

In this moment, I am not sure if I should rage or cry. I know I need to keep hustling, but instead, I spend the next five minutes ranting about the multitude of reasons why our shared patient will never march up to the nursing desk and demand food. I rattle on about the long history of racism and mistrust between our communities and government institutions such as our hospital, the power imbalance between patient and provider, often enhanced greatly by limited health literacy, language barriers and cultural differences. I notice her face shifting, softening. I carry on. We talk about poverty, trauma, residential schools and how this plays into every encounter, every single day in our hospital. I paint a picture of how a patient moves through the system from the first presentation to the nursing station, onto a plane with little prior notice, before ending up in our department many, many hours later, usually hungry, alone, exhausted and often without any belongings.

“I didn’t know,” she admitted. I laugh, ‘That’s why you think I’m always crazy running around the hospital at all hours scrounging up iPhone chargers, warm blankets, sandwiches and shoes!’ She smiles back, and for a moment, there is a collective remembering of why we chose our professions – why we still keep showing up. Despite the sinking ship and the chaos that surrounds us, together I know that we both can still hear the orchestra playing.

In medical school, I sat through countless lectures on medical professionalism, health advocacy, ethics and boundaries. In usual form, tidy notes were taken, passages memorized and exams passed. When I arrived in Sioux Lookout as a naive, bright-eyed third-year medical student, I felt confident in my knowledge, full of excitement and wonder about this new adventure in medicine. I was brimming with textbook wisdom of how things ought to be.

On the ground, the tidy boxes of colour-coded notes floating in my brain were soon in disarray – my patients and colleagues as my new teachers, rapidly dismantling my learned ideologies. My passion for medicine had always been grounded in the humanity of it all and I immediately delighted in watching my newfound mentors demonstrate what health advocacy truly looked like. Theoretical, academic treaties suddenly felt useless in the face of what our patients were encountering on a day-to-day basis. Of course, boundaries in medicine are vital to ensure patients and providers are safe, but what I witnessed daily in the provision of medical care in those early years in Sioux Lookout was so much more than order sets and antibiograms.

Practicing medicine meant noticing that it was a patient’s birthday on her post-partum visit with a medically complicated newborn in tow and hastily passing around a birthday card to be presented with the patient’s favourite drink from the cafeteria. It meant bringing a treasured Tim Horton’s double-double to a hospitalized Elder without family nearby. It meant giving rides and gathering newborn items for a struggling family. It meant pulling out your VISA after hours to pay for flights in order to reunite family members after an unexpected tertiary care centre transfer and birth, long after administrators and management had gone home. It meant spending extra time on the phone with the funeral home and lab to ensure the fetal remains of a woman’s miscarriage were safely brought home to her community for ceremony. It meant looking beyond the diagnosis and truly hearing the patient’s story, taking the time to ask ‘what has happened to this person in their life to have brought them to this place of struggle’. It meant partnering with communities to relentlessly fight for medical equipment, mental health services and basic needs like housing, clean water and access to education.

While in medical school I was taught to maintain professional distance, uphold patient-physician boundaries, never get too attached, limit my emotional expenditure and dissociate to provide optimal care. Yet, what I saw every single day in practice in Sioux Lookout did not match what I had learnt in my lecture hall. My colleagues unabashedly pushed through the confines of those tidy boxes without a backwards glance. Unapologetically, tirelessly and relentlessly advocating for their patient’s needs – both big and small.

As a green medical student, I was shocked at their audacity to challenge what I had been traditionally taught about boundaries, and professionalism in medicine. It was profoundly formative as patients and colleagues revealed to me how intimately intertwined medicine and advocacy were. All the antibiotics in the world would not do a damned thing in treating a patient’s post-op wound infection if there wasn’t also stable housing, as well as addictions and mental health services that were equally prioritized.

Last winter, I took my first sustained break from medical practice in Sioux Lookout since the beginning of my career as a newly minted MD, straight out of residency eight years prior. Despite locuming in a new community with perfectly lovely patients and colleagues, I struggled with nightly feelings of emptiness at the end of my clinic days. Something just didn’t feel right. My grief and longing for my colleagues and work in Sioux Lookout forced me to peer deeply inwards and question what was it about my medical practice that I missed so profoundly. Could it be that despite the chaos, through the most challenging patient encounters, these acts of empathy and advocacy, both big and small bonded us, both patients and physicians together, building resilience and connection? Could it be that in making an effort to truly see our patients, we were perhaps not the only healers? Could it be that through these acts, conceivably, our patients were, in fact, the ones healing us in return?

These days, headlines trumpet our crumbling healthcare system and not a shift passes in my clinical work that I don’t see its effects on patients and families. Now back in British Columbia working at the local urgent care centre, virtually every patient encounter begins with the same troubling statement: ‘I don’t have a family doctor anymore…’ Patients struggling with complex medical and social concerns, attempting to navigate and understaffed, underfunded medical system with no one in their corner. Family physicians, the quarterbacks of the medical ‘home’, have been chronically underpaid and grossly overworked for decades. Understandably, post-COVID, burnt out, they are now quitting in droves and very few brave souls are entering this line of work after medical school to take their places.

To put it simply, it’s a mess and I am worried.

Worried, of course by the obvious medical consequences – delayed cancer diagnoses, rising mental health crises and drug overdoses, surging cardiac and cerebrovascular events while preventative health disintegrates, but even more desperate, as staffing shortages climb and our human resources continue to drain, lack of empathy and compassion fatigue prevail. Humanity is the first to go at the bedside and this is what I’m most fearful of. Of course, the cog will continue to turn, thrombolytics will be administered, and scalpels will excise cancers but If we cannot continue to connect with each other and to our patients through empathy and story, the relationship of bidirectional healing and reciprocity will wither and I, for one, know I will not be sustained in this profession as a result.

In the delivery room, the newborn wails, calling out its first few breaths against his mother’s chest. She smiles quietly, holding his slippery body tightly. The nurse administers medication to prevent bleeding, records vitals and swiftly tidies the evidence of the birth as I examine the baby, a pink neonatal stethoscope against the tiny chest, smiling at the woman as I listen to the usual thrum of the babe’s heart. We had met many times prior to her delivery – her sixth little one arriving on the heels of her two-year-old’s birthday back home. She was here alone, her partner providing care for their family with no one else reliable to either come to Sioux Lookout or provide childcare back home, hundreds of kilometres away. Reaching for her iPhone at the bedside, I ask if she’d like me to take some photos to send home. ‘The camera is broken,’ she responds matter-of-factly not breaking her gaze at her new babe’s howling face. No photos, no FaceTime, no bridge to share this momentous occasion with those whom she loved. My heart squeezes tightly at the loss. Within minutes, my patient becomes my newest Facebook friend and with permission, intimate photos of those first precious moments move across the ether from my phone to hers, a boundary-crossing that surely would not have been condoned by my medical school professors. But there it is. A connection, for a moment, not between doctor and patient, but between mothers, between humans. A gift to both of us.

This is the medicine that will sustain us and I am certain, this is the medicine that will continue to heal.

“I think I’m finally ready to start medication.”

I don’t notice, but a small pile of fingernails litters the floor at my desk like bones in a long-forgotten graveyard. Unconsciously, I claw at each nail, cuticles raw and bleeding – an anxious habit learned long ago from my mother. I shift uncomfortably in my chair, trying to keep my voice even. I’m prickling with sweat. I’m talking too much, uncomfortable with any moment of silence during this phone consult with my family doctor.

As a physician, counselling patients about mental health is a daily part of my job. Yet, what most people might not know is that physicians, for the most part, suck at being patients themselves. Case in point – it’s taken me over a year to make this dreaded phone call and I’m nervous as hell to speak to my lovely GP about something that is as common in family practice as dealing with a sore throat or an ingrown toe.

For over a year now, I’ve been quietly contemplating starting an SSRI – a class of medications used to treat anxiety. My reluctance, however, was informed by my deeply-rooted, core belief that no problem cannot be resolved by simple hard work, perseverance and a healthy dose of self-sacrifice. Work harder, push through and above all, keep your head down and just keep going. These ideals, ingrained into my childhood consciousness, have certainly served me well in medicine and continue to still do in. Who wouldn’t want a micromanaging, hypervigilant physician with an insatiable work ethic? But after two years of counselling, mindfulness and regular exercise, I was still unable to play.

Yes, play.

For years, all Henry has ever wanted to do with me is play LEGO. His absolute favourite activity, each morning he wakes me with the same plea, ‘Mom, will you play LEGO with me?’. Coffee in hand, I would sit amongst the sea of colourful blocks scattered across his bedroom floor, anxiously scanning the extent of the mess. With Henry’s coaxing, I would pick up a LEGO man and participate, under Henry’s direction in the imagined scene. Yet, always within minutes, without intention, I would abandon the game and find myself sorting the hundreds of LEGO pieces, reattaching minuscule arms onto limbless torsos and corralling escaping blocks back into the bin with the same desperate monocular focus I applied in my work. Disappointed as always, Henry would gravely inform me of his dismay. ‘Mom, you’re not playing,’ he would lament, wandering off to find Alice instead and each time, no matter how shitty of a mother I felt, I could not stop bringing order back to his playful, imaginative LEGO world. In truth, it broke my heart each and every time.

Smiling kids on the ski hill, photos documenting camping adventures across the Rockies, scenic hikes with picturesque mountainscapes in the background – the feed of photos, as always, tells only one small piece of the story. This past year has been full of excitement, hard conversations, difficult transitions, loss, grief and new adventures. While we are incredibly privileged to have been able to move our family to Kimberley, named the best small town in BC by the CBC, this year of transition for our family has been disquieting, to say the least.

I mourned the loss of our first family home on the shores of Abram Lake – the proprietor of all of our young family memories and grappled with the dissonance I felt when imagining another family flourishing within its frame of cedars, pine and untouched shoreline. The anguish of abandoning our plan to build a fully passive home on the 36 stunning acres stretching before the Norwester mountains on the outskirts of Thunder Bay and the loss of the two years of energy, planning and anticipation attached to this project was particularly painful for Blake. At the same time, I struggled for months with deep feelings of grief and loss of what our decision to move away from my job in Sioux Lookout meant for me as a person and as a physician. If I wasn’t going to be the passionate full-scope, rural family physician toiling away in the trenches in the North, then who was I? And if I’m going to be truly honest, if I wasn’t working in the most challenging capacity that I possibly could, would I still be worthy of my job as a physician? The farcical fear of scarcity – would I be enough if I was just a simple family doctor?

Above all, Blake and I circuitously debated our decisions and how they would affect our kids, our family’s future and our collective happiness. How would Henry and Alice’s lives be different if we stayed in Northwestern Ontario, possibly to their detriment, in order to keep Mom’s dream job alive? We exhausted lists of pros and cons, hashed out financial scenarios in Excel spreadsheets and leaned heavily on our close friends for advice.

As you can imagine, my cuticles have not been pretty over the past year and the rosy picture on social media notwithstanding, I was struggling. Despite doing all of the things I routinely advise my patients to employ in their day-to-day lives to improve and maintain wellness, I felt like I was constantly spiralling, tearful and brimming with fear. I knew I had to finally make that dreaded call to my family physician. I couldn’t help but ruminate on this constant, nagging thought – what if there was just this one thing that never I had the courage to do? This one thing that could be the difference between a mom who could be present, who could be still and who could play?

Almost six months in and my nails are still ripped to shreds, but I have noticed slow and steady gains. Once this summer, I didn’t have time to fully finish weeding the garden and I just… left it! Can you imagine?! All joking aside, although life still is throwing us curveballs, this summer Blake and I have survived two different moves – one in Sioux Lookout and another from Ontario to BC that required two different cranes, a 40-foot shipping container, two cars and one trailer with our marriage intact. Although we struggle, as all couples do, our ability to manage these rough waters together has massively improved with my step back from the metaphorical ledge. Above all, although I still grapple with the chaos of the playroom, the LEGO dudes continue to be limbless and the LEGO bin is a jumbled mess and despite the disorderliness, I just think I might be ok with it.

As we all navigate transitions this Fall – back to school, maybe a new job, all the while continuing to face financial, political and climate uncertainty in our world, I wish you all the courage to get the help that you might need to be a more stable partner, parent, colleague, family member, friend and, most imperatively, a more grounded you. And if the thought of this brings you to ferociously whittle your nails down like me, remember, doctors are people and patients too. The universality of our collective mental health struggle is real. You are not alone.

Home

*Trigger warning – birth trauma*

My heart in my throat, I paw at my cellphone in the darkness. The piercing, recognizable ring linked to the hospital is startling.

“It’s Dr. Sprague,” I mumble.

“Labour room one. Grandmultip. Just arrived. Fully and pushing,” comes the crisp reply.

Mere moments ago, I had been slumbering like the dead. After three successive nights on-call for our local maternity practice, it had taken me seconds that evening to drop heavily into bottomless sleep, fully dressed in a clean pair of my hospital scrubs. My night uniform, ready for action at a moment’s notice.

With no time for even a quick bathroom break, I stumble along the darkened path to the driveway. As always, my brain rests briefly on the image of my husband and children sleeping soundly, unaware my night’s interruption.

Before my eyes are even fully opened, I jam the groaning SUV into reverse and am speeding down Abram Lake Rd. Blake would certainly have had something to say about the rapidly rising speedometer, but I know I have mere minutes before this baby is born. The junior nurse, just barely through her orientation to our busy obstetrical unit would have much to say if she was required to attend the delivery without a physician present.

6 minutes, door to door. I know the route by heart and at 4am, I drive it like a Formula One racer – my body leaning into corners, my leaden foot on the gas. At this time of night, deer are more populous than cars in our remote, northern Ontario community of Sioux Lookout. Not a single traffic light to slow my course. Only the sole stop sign on 7th Ave which I vaguely slow down for at night on my way to the hospital. So ingrained in the habit of optionality, I once was pulled over by an earnest OPP office driving the kids to the school. “You know that you just drove through that stop sign going at least 20km/h, right?” he had questioned me through the driver’s side window. The kids, observing wide-eyed in their matching car seats. I had had to quickly correct myself before I had blurted out that indeed, it was a bad habit of mine, having had repeatedly blasted through this exact stop sign for many years on my way to catching babies at 3 am.

Luckily, no deer or cops to hinder my nighttime commute tonight. In the final 100m, I ready for the closing leg of my journey to the delivery room. I undo my seatbelt and lasso my name badge around my neck, screeching to a halt in the patient drop-off parking in front of the ER doors. Racing on foot now, I sprint past the COVID screeners encased in their clear, acrylic cage, snatching a mask on the way by. Down the long corridor framing the courtyard that by day spills delicious sunlight into the sterile space. Tonight, the lone custodian perched high atop the droning floor waxer nonchalantly nods in my speeding direction. He’s seen this routine many a time.

Wrestling my bedhead into a ponytail, I slow my pace briefly as I pass the medical nursing desk. I certainly don’t want to cause undue alarm to the bevy of night nurses resting their heads on their desks, flannel hospital-issued blankets draped over their shoulders. Then galloping again for the last few meters before hurtling my body at the metal double doors to the Maternity Unit, my fingers still caught in my long tangles.

Inside, I am met with silence. No wailing newborn. Relief in the rapid realization that I have made it in time, I shed my jacket haphazardly at the cluttered nursing desk. The doptone cuts through the stillness, announcing the fetal heartbeat through the partially opened door of the labour room. Thrum, thrum, thrum, thrum, thrum. 160bpm I note, recognizing the cadence of its rhythm. A moment later, the wail of the birthing mother quickly turns to low guttural grunting. 6.5-sized gloves stretch over my sun-wrinkled hands and soon a screaming babe is lifted to his elated mother’s chest.

A new life.

In some capacity, I have always known that I had wanted to do maternity care. Prior to medicine, midwifery had been my path, but the limited scope hadn’t felt like the right fit. I yearned to work remotely and to use my privileged position, my knowledge and skills to serve marginalized families and communities. I wanted a generalist practice with a broad range of skills. I didn’t seek to solely attend to low-risk women through their pregnancies but also wanted to assist with the woman’s older child’s asthma, her partner’s substance use disorder, her infant’s reflux and her own multitude of medical issues. So rural family practice it was. An immediate, lusty love affair.

During medical school, I intentionally spent eight months of my clerkship in the community of Sioux Lookout. A regional hub, striving to serve the health needs of 33 Indigenous communities of the surrounding Anishinabe Treaty 3 and the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (Treaty 9), a combined area spanning West to the Manitoban border and North to the James Bay Coast. Although my growing passion for rural medicine was solidified on the inpatient unit, recognizing the physical exam findings of rheumatic heart disease or in the fly-in nursing station, stabilizing an ATV trauma, what I fell hard and fast for was obstetrics. Dr. Dooley, my then preceptor, now dear colleague, used to amiably grill me for skipping out on ER shifts in order to follow women through their deliveries. I had drank the elixir and was hooked.

In medicine, there are certain specialties that cause a definite polarizing effect. Obstetrics is one of them. There truly is no middle ground – either one loves it or hates it. While to the layperson, delivering babies into the world may superficially seem like an easy, joyous way to spend one’s working life, the truth of it is attending women in the most vulnerable points of their lives brings many dichotomous feelings. Passion and fierce love for the job abutted against the constant interference into one’s personal life. A tether to one’s phone, car and hospital so short that it curtails most all of life’s treats: a glass of wine at dinner, a lengthy ski in the bush, a solo trip to the library with the kids, an uninterrupted night’s sleep. Yet the rush of the privileged access into a woman’s most intimate moments is almost inexplicable. Strange indeed, the devotion to an occupation that induces terror so deep while at the same time bringing tears of relief and joy at the beauty of it all. After hundreds of births, somehow it all still feels just like home.

In the basement home office, files of green pieces of paper are categorically organized by date. Binders upon binders of labelled billing sheets representing each delivery attended over the past seven years. “How many?” Blake wonders. I shrug. I’ve never counted. Hundreds of stories bleed into each other often hastened by sleep deprivation-induced amnesia. Details blur, but inkblots of tragedy, comedy and elation stand out. Pre-pandemic birthing rooms packed to the gills with aunties coaching labouring women in their language, partners steadying iPads connected to family hundreds of kilometres away watching the joyous arrival over FaceTime, toddlers snoozing in strollers or makeshift beds in the corner, unperturbed by the noisy arrival of their newest sibling. A memory of unflappable maternity nurse, Coral, one arm supporting the leg of the birthing mother, while nonchalantly catching an excited sibling as he near tumbled headfirst from his post on the pull-out chair in the corner with the other.

I loved this job. Despite the depth of the personal sacrifices it took, I loved it without reservation and I was good at it. This past year in BC on our family’s East Kootenay adventure away from my medical home has so deeply reinforced these sentiments.

Yet there is one birth that will never erode at the edges with time. One that will remain painfully and nauseatingly clear for the rest of my working days. One that shook my entire being, rocked my confidence and demanded reconsideration of this beloved career. One that so acutely comes to focus as I ready for my return to Sioux Lookout and re-entry into my obstetrical practice. Nearly a year ago, in six minutes, my bond to this job became utterly and immutably frayed.

In obstetrics, there is little that can categorically bring a care provider metaphorically to their knees more swiftly than a shoulder dystocia. An obstetrical emergency, in simplistic terms, a shoulder dystocia is the time-warped space between the delivery of the baby’s head and the body that refuses to follow. When seconds stretch to hours in the provider’s mind as the baby’s shoulders catch stubbornly against the maternal pelvis. Bone upon bone. Desperation mounts with each passing minute of this precarious stalling of time between life and death before life has yet to even begin. Without vital blood flow through the umbilical cord, nor the ability to fully transition to extra-uterine life, generally, the fetus has roughly five precious minutes before asphyxial injury or worse yet, death, ensues.

If this doesn’t induce sweaty palms at the mere description of it, ask any obstetrical provider about their worst experience with shoulder dystocia and watch closely. Even the most hardened midwife, grumpy obstetrician or senior labour room nurse will not be able to mask the cloud of recollected fear that will pass through their eyes at the pained remembrance of it.

In our maternity practice, due to the remoteness, the high volume and acuity of our patients and the lack of specialty providers, our group of family doctors work as a tightly-knit team with each delivery attended by two nurses and two physicians – one for the baby and one for the mom. This system also provides a relative safety net for each other, a sense of security that you will always have a colleague to back you up. Working in a team also safeguards against burnout as feeling alone and unsupported in medicine is a surefire fast-track for the exit sign.

For years, as a newly minted physician, when I was up shit creek without a paddle (a plummeting fetal heart rate, a complicated perineal laceration, a stalling labour..) while attending the woman at the bedside, relief would flood the moment I saw my colleague’s feet at the doorway, peeking under the privacy curtain. Dr. Bollinger’s muddy Blundstones. Dr. Finn’s scuffed and worn red boots. Dr. Dooley’s ironic skater shoes. Help had come.

As time passed and younger graduates were folded into our group, I suddenly found myself as a ‘senior’ colleague providing support and advice to greener colleagues. On the day of that fateful delivery, I was working with a junior colleague, bright and skilled, as her aged and wrinkled advisor.

It was mid-afternoon, the end of a 30-patient clinic nearly insight when I had been called to a delivery that my colleague had been attending throughout the day. I had met the woman in labour many times throughout her pregnancy which had been largely uncomplicated. Without too much forethought, I trotted to the delivery suite, donned my gloves and, as the ‘baby doctor’, went through my routine of checking the resuscitation equipment. A flip of the switch to turn the oxygen on, the suction noisily coming to life, the seal of the bag valve mask tested against my palm, the laryngoscope light blinking brightly. As usual, all was in order.

As I turned away from my post at the neonatal warmer, I took in the scene before me. The woman labouring in the bed, surrounded by nurses who wet her dry lips tenderly, gently wiped the sweat off of her chest and murmured encouragements. My colleague poised at the foot of the bed, attentive, focused. The partner standing between me and the tableau of female care.

The partner, I had realized was someone I had never formally met despite our town’s sparse population. With his back to me, he shifted nervously from side to side. For a brief moment, I mindlessly contemplated his frame: stocky, solid, built like a rugby player. I didn’t have to extrapolate my growing fears of the inevitable before it was urgently a reality before me. With the next push, my colleague gently guided the baby’s head across the perineum.

Time zero.

In obstetrics, the clinician’s first inkling that trouble might lie ahead is called the turtle sign; a retraction of the head against the soft tissues of the woman, a turtle attempting to retreat into its shell. In reality, it appears just as you can imagine it.

I locked eyes with the nurse, our gaze communicating what we did not need to say aloud. She lowered the head of the bed while quickly pulling the woman’s bent knees up and outwards.

McRobert’s maneuver.

45 seconds in and I hover tightly at my colleague’s left shoulder as she tries to negotiate the baby’s shoulders through the birth canal to no avail. I navigate the delicate dance of allowing her to be independent, to learn, and to have the chance to succeed on her own against my pressing urge to micromanage.

60 seconds. Either I push my way through or my colleague steps aside, I cannot recall. As the senior of us two, I know in my gut, it’s now my turn to step in.

In medicine, like pilots in virtual simulation labs, we rehearse emergencies repeatedly to avoid the folly of our own fallible nervous systems. “At a cardiac arrest, the first procedure is to take your own pulse” states the 3rd law of Samuel Shem’s House of God. Stay calm. Detach. Our hands smoothly go through practiced maneuvers while our minds claw at the door in panicked desperation to be anywhere but in charge of the medical emergency before us. It is not uncommon for physicians to retroactively describe total dissociation, an almost apparition-like perspective, watching their bodies run a code or manage a trauma without anybody at the helm. Auto-pilot. A ship on cruise control while the captain jostles for a seat on the lifeboat.

“Suprapubic pressure, to the maternal right,” I hear myself bark. Her hands entwined over each other just above the pubic bone, my colleague forces the weight of her small frame in a rocking motion against the mother’s abdomen, willing the baby’s shoulder to be thrust out of its firm entanglement.

Rubin then Woods screw maneuvers. My hands move through practiced rhythms in an attempt to rotate the entrapped shoulders.

3 minutes.

I fight panic as I then fail to gain purchase on the hyperextended posterior arm, the next step in my drilled algorithm.

“All fours,” I hear the command leave my mouth more solidly than I feel. The Gaskin maneuver. So reliable from my midwifery days, never once failing me in coaxing a baby out of the birth canal. My growing confusion and dread when it too, fails.

4 and a half minutes. Sweat now pours between my breasts.

The woman, heaved hastily again to her back by the nurses in our now increasing desperation.

I will my hands to steady as I widen the opening of the birth canal with my scissors and start the sequence of maneuvers once again.

“Call anesthesia”, I shout. I know now that if I can ever extract this child from his mother’s body, he will most definitely require full resuscitation, if not worse.

My arms, strong and toned from years of weight training, feel like lead, elephantine and useless. My rapid breath catches, hiccuping along with my racing heart thrumming in my chest.

5 minutes. I rack my brain. There is no one else to call for help. The colleague who provides c-sections is at least 15 minutes away. At best, we could get to the OR in 30 minutes. It would be too late by then. At seven years into practice, I am the most experienced physician in obstetrics in the hospital.

I am the end of the line.

“I can’t. I can’t,” I hear a voice rasp. I don’t recognize it as my own. My eyes fly wildly about the room. Searching for what, I’m not sure. My hands continue desperately in their efforts. Attempts to break the baby’s collarbone to fold its shoulders into a smaller diameter are to no avail.

In my limited years of practice, whenever I have managed a difficult shoulder dystocia, there is always a small part of my brain that whispers, “Will this be the one? The one where the baby dies on your watch? In your hands?”

6 minutes. I hear the whine louder and louder. This will be the one. This will be the one.

Then for no rhyme or reason, the shoulder finally gives way to my hands’ insistent pleading. After six and a half minutes, just a few grams shy of 5 kilograms, he is born.

Sweat drips into my eyes as I peer down at the silent, flaccid baby between his mother’s legs. My hands shake violently as I silently cut the cord and shuttle his lifeless body to the resuscitation warmer. Pushing breath into his quiet lungs, my anesthetist colleague is suddenly at my side. ‘”Breathe, Celia, breathe,” I hear him say (later, he tells me I was breathing at a rate three times what a normal adult would breathe at rest). We work seamlessly until the babe finally takes his first breath and a mewing attempt at a cry.

I resist the urge to vomit.

Hours later, I watch through the glass of our makeshift mini NICU as the GP-anesthetist adjusts the CPAP breathing mask over the babe’s bruised face. He is breathing spontaneously now, a good sign. An IV line is anchored securely into his plump foot. The nurse takes his vitals. My chin grips the receiver as I run through the case with the nearest pediatrician, over 500km away. As I end my rattling history with the baby’s most recent numbers and bloodwork results, momentary silence ensues. “Six and a half minute shoulders,” the pediatrician repeats. “I’m so sorry.” An unspoken understanding of the terror that I don’t include in my case presentation. He does his best to reassure me, but we both know that the true outcome is still unknown.

Later, for weeks, as I lay in bed, I replay the sequence over and over. What could I have done differently? Why wasn’t I successful initially? What if I am not competent to do this work anymore? What if the babe had died? I contemplate nightly alternative career options. Librarian? Summer camp director? Canoe trip guide?

I don’t want to hold a baby’s life literally in my hands anymore.

I am just human.

Just a human.

As it happens in small towns, in the months that followed that afternoon, I have run into this family numerous times, getting updates about his pediatrician’s visits and watching him grow as a perfect, healthy, beautiful, blue-eyed squish of a baby. In a recent post on his mother’s social media feed, he peers keenly into the camera with a heart-breaking smile, his face smothered in his lunch. ‘To think we ever worried he wouldn’t meet his milestones!’ his mother has captioned the photo. It’s impossible to look away but my vision is clouded in tears. The joy and the pain, terror and relief, death and birth. This job, full of its impossible dichotomies. My medical home. And inexplicably, I can’t wait to get back at it.

For My Daughter

Through my laptop speakers, classical music preludes the series of instructions that follow: ‘Arms up, toes out, and plie!’ directs the instructor. On the screen, I watch her leotard-clad body intently. As she moves, I follow, mirroring her balletic gestures. Her hair is pulled back neatly and her slim arms gracefully direct her small charges – a posse of pink-tutued kindergarteners encircling her.

It’s Monday, the day that Alice is usually dropped off outside the local dance studio for an hour of ballet and tap dance instruction. However, true to the ongoing COVID experience, here I am, keenly learning the choreography of my six year-old’s year-end dance recital piece over Zoom with a snotty-nosed Alice beside me.

From the corner of my eye, as Ms. Jacqui demands more plies, I see that Alice’s motions are certainly not even in the realm of ballet. I stop and turn to Alice quizzically. ‘Alice, you need to be following…’ I trail off as I realize what is happening. In her full ballet attire, tights, tutu and all, Alice has (of course) removed the requisite bun from her hair and is jumping wildly across the mat. With her flaming locks askew, she kicks and karate chops the air with exuberant ‘Hi-Yah!’s. Without a care in the world, she rehearses her self-taught ‘ninja moves’, seemingly unperturbed by the ballet class that she is to be following.

I want to scold her, to tell her to stop her nonconformity and pay attention. I don’t want her to be called out by her instructor for not listening and worse, I don’t want to be labelled as the mom who can’t control her quirky ninja child.

The classical piano notes continue to flow gently through the room, juxtaposed against Alice’s brusque, high-energy movements. I hold my tongue and watch with awe. I want to freeze this moment into my brain, protect it and hold it in the safe of my mind. This child, just as she truly and fully is.

Alice celebrated her 6th birthday last month amidst a flurry of streamers, cupcake-fuelled skiing and t-bar laps at our local hill. It has been a challenging year for Alice, full of transitions, ups and downs. Her fiery temper raging at home oscillating with her extreme shyness and near muteness at school. Her saint of a Kindergarten teacher, coaxing her gently to break out of her shell with her peers, encouraging and supporting her day after day in the laborious process. Then, the outpouring of emotion at home, her frustrations, fears, anger and hurt bursting forth after being held, wound tightly within her throughout the day.

Through all of this, however, her charismatic, spunky self has continued to expand and unfold before us.

Despite my suggestions of the classic, singable Disney ballads, she routinely favours the grunge-rock theme song from the Japanimation show, Bakugon for the car commute to the pool. For library day, she independently selects titles from her favourite Zombie graphic novel series. LEGO is her preferred toy, but please, not the girl-branded ‘Friends’ LEGO, ‘because it’s not the REAL LEGO!’

With Henry, she loves him desperately, but will wrestle him to submission with brute force and without a hint of remorse whenever a parental eye is turned. To school, she will pair a Ninjago t-shirt with rainbow and heart-spotted sweat pants. After dinner, she habitually strips down to her underwear and flies full-tilt across the kitchen and living room repeatedly for her nightly ‘ninja training’, exercises that must be executed to fulfill her wish of becoming a ninja-librarian someday.

My Alice – full of seesawing emotion, ideas, stories, kindness and love.

I watch her with wonder because I know at one point, I was just like her. Unfiltered, unaware, oblivious and unconcerned.

When does it happen? The shift from the free to the caged? As a parent, will I see the sequence unfold in front of me? At what point do we come so acutely aware of societal, cultural and familial expectations, conditioning us into submission?

When I was about eight years old, I have grey and cobwebbed memory of pulling out my Mom’s old typewriter from the storage room. Alone, sitting among boxes of halloween costumes and photo albums, I sat down, keystrokes clacking discernibly, typing up a ‘pact’ with myself, promising I would do 25 sit-ups each day for the rest of my life. A certificate I then signed in my grade 3 cursive, just to make it appear more official.

This was also around the time I began wearing a t-shirt over my bathing suit to cover my perfectly rotund abdomen whenever anyone other than my family was at the beach. At skating competitions, before taking to the ice, my arms instinctively were used to shield my body, so nakedly exposed in my spandex. I despised testing days, where we were required to step solo onto the expanse of the ice surface in our competition dresses. No sweaters to hide the soft bulges at my sides, pinched and spilling over the unforgiving, wide elastic band of my tights.

Not long after, on my walk from school to the rink one afternoon, I recall stopping at a magazine store. While paying for my selections, the middle-aged clerk had paused, holding up the covers of various weight loss magazines. ‘I hope these aren’t for you, young lady,’ she had said. ‘You certainly don’t need to be reading this nonsense!’ My middle-school self begged to differ but had offered a mumbled excuse instead.

Looking back, at these disconcerting memories, I was only a few years older than Alice is now. A child. Where in the hell had I already gotten the message, so loud and clear, that I wasn’t perfect just the way I was? Before I had even reached double digits, how had I known so undoubtedly that, as a girl, I had to make every effort to be smaller, thinner, prettier in order to be in the world?

Uncomfortably, my school-aged memories are peppered with recollections of heartbreaking feelings of shame for how my body appeared and worse, the knowing that somehow I was increasingly failing against what I felt deeply was the ideal image of a young woman’s body. The incongruousness of meticulous calorie tallies in my childish pink diary, so carefully hidden away with its flimsy lock and key.

By high school, I had wholeheartedly internalized an inner fire to perfect whatever came my way. Somewhere along the line, I had learnt that in order to be worthy of acceptance and love, I knew I had to hustle. And hustle, I did.

At my high school graduation, with numerous academic accolades, the ‘Best All-round Female’ award and pre-med acceptance to all of the Canadian Ivy League universities, I had gotten the routine down pat. Perfect, perform, please. But who exactly was I pleasing?

At Queen’s, my torturous self-expectations sky-rocketed and along with it, more distorted ideas of self-image and eating behaviours. Twenty years later, I still can’t bring myself to explicitly write the depth of the despair precariously set so heavily on that young woman’s shoulders. She was so deeply hurting and despite all of her so-called achievements, she was so incredibly alone.

Powering through a rigorous pre-medical degree, volunteering on various committees, holding down a job at night to fund a spot on the local competitive skating team; on paper, I was doing it all. Yet whenever my parents called, I did all I could to keep the conversation brief lest the tears would reveal the reality of my suffering. I couldn’t bear to let them truly see through the facade. I wanted so desperately to be perfect, to make them proud.

Strings of gold, her tangled locks cling to her flushed cheeks and fan around her face like a haphazard crown. Her slumbering profile is illuminated by the neon pink hues of her nearby night light. Her breath is soft. An army of stuffies, combined with stacks of picture books border her slackened body. She sucks her fingers, a remnant behaviour from infancy. I can’t help it, but she’s irresistible. I tuck in beside her, my head resting on a hot pink plush unicorn with bulging, hard plastic rainbow eyes. Gently rubbing her back, I whisper my fears through the darkness. ‘It’s only a matter of time,’ I worry anxiously into the night.

Only a matter of time until my daughter is awakened to the distorted beauty ideals of our culture and made known to the fact that seemingly, a woman’s face is only acceptable if primed with makeup, injected with fillers and grossly falsified by filters on social media feeds. Only a matter of time until she is taught what it means to be a ‘good girl’ in our world; quiet, unquestioning, selfless, and what burdens she will carry as a woman in our society. Only a matter of time until she is conditioned fully, schooled in the weight of gendered expectations. All of the ‘shoulds’ suffocating her life’s dreams. ‘My daughter, if only I could hold you here, just as you fully are for eternity,’ I whisper.

How might our lives look different if we all existed as our six year-old selves? Bold, unwavering in our self-appreciation, unquestioning of our talents, beauty, and strength. Self-confidence abound. Unfiltered in our convictions. Centred, settled and absolute in the obvious love that surrounds us. True to our fully, uncaged, non-contorted selves.

I wonder too how my life might have been different.

So, to my daughter on your 6th turn around the sun, I must confess – I simply have no idea what I am doing as your mother and I must apologize in advance for all of the future therapy that I likely will bestow upon you. I don’t have all of the answers nor the parental manual on how to raise the girl and woman I know you will be, but damn it if I won’t die trying to encircle you in unconditional love. Damn it if I don’t do everything in my power to keep it all at bay for as long as possible. Damn it if I go to every length in armouring you in the knowing that you are whole, perfect and fully loved just as you are, tutu-wearing ninja moves and all. And damn it if you won’t see me trying, session by session working away at my own demons, breaking down the walls of uncomfortable memories, chasms of hurt and shame brick by brick.

‘Yes, it’s only a matter of time’, I whisper. ‘But damn it, my girl, if you won’t be ready for the inevitable battle.’

Sibling Love

“I swear you can hear their eyelids open,” Blake joked one morning after I had recounted the tales of the preceding night with two babies under two. As usual, he had slept on soundly through Alice’s nursing sessions and Henry’s night awakenings, protesting the confines of his crib.

He wasn’t wrong. When I became a mother, along with these creatures that had grown inside me, a new intuition had grown in parallel. A connected sense that didn’t meet any worldly logic.

Aside from a low-tech, beat-up baby monitor that we used when we frolicked on the beach while Alice or Henry napped, I never used a device to supervise our sleeping babes. I didn’t understand the need to watch them endlessly on a one-inch screen. I inexplicably felt they needed me before they ever made any sounds.

Now, no longer babies, this maternal superpower continues.

Through the heavy, velvety curtain of sleep, my eyes flicked open. Pulling my earplugs from my ears, I already knew that one set of pint-sized bare feet would be creaking through the house. Propped up on one elbow, I held my breath and listened searchingly. Nothing. Blake slumbered on beside me. Clumsily yanking on my slippers, I slipped by Alice’s empty bed knowing exactly where I would find her.

Over the years, like clockwork, Alice had been waking with complaints of loneliness through the ungodly hours of the night. Always, her fleece dragging along beside her, she would search for me in the blackness and beg for companionship. Nightly, I would stretch out on the floor beside her converted toddler bed, room for only my head to perch uncomfortably on its edge, a hand in the space between her shoulder blades, waiting for her breathing to slow. Night after night. If her twilight quest revealed an empty space on my side of the bed, having been called for a delivery or working an ER nightshift, she’d simply help herself to its glorious luxury, slipping in beside Blake, who remained blissfully unaware that any night happenings were occurring.

Tonight though, despite her bedtime demons, she hadn’t come in pursuit of me.

Over the preceding days, Blake and Henry had taken off for a multi-day father-and-son winter camping ski trip to ‘rip the pow’, as Henry would say casually. Fueled by endless hot chocolates in the camper, they snuggled like cocoons in their winter bags, forewent all personal hygiene tasks and gobbled pizza at every meal.

Alice and I were having an equally comfy extended weekend of snuggling in bed, barricaded from the world by books forming a U-shaped fortress around us. We promised to just wear PJs and went outside only to drink in the powder that fell endlessly from the sky. But despite our seemingly joyful time together, every few hours, Alice would pause her activity and inquire about Henry’s return. How many more hours still until the boys came home, Mom?

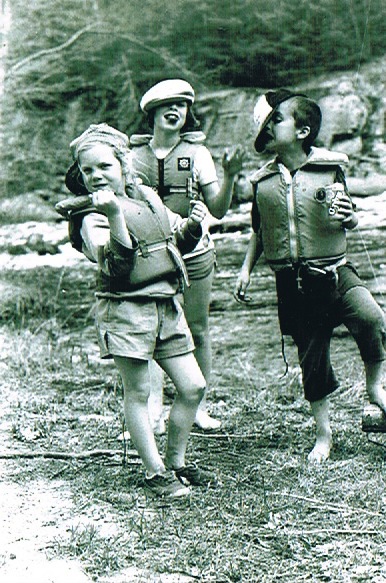

It was the summer of 2015 and our bare legs stretched out over the driftwood-strewn beach as we regarded the Hecate strait with wonder. The only souls for miles, an abandoned quiet encircled our unconventional date night. Behind us, an eight-month-old Henry slumbered in our three-man tent as dusk crept up to meet our toes. Red wine sloshed in our travel mugs and our backs slackened further against the fallen ancient cedar backrest with each sip. Haida Gwaii had always held a treasured place for Blake and I. Our four-month stint in Masset during my residency had been the best season of our marriage. I had watched orcas pass by through the hospital’s front windows while Blake foraged for salmonberries, caught specked trout in the rivers and formed deep relationships while lending a hand in the building of a longhouse with a local carver.

With Henry newly on the scene, we had made the trek to the most western part of our country to recreate the magic on a two-week-long camping road trip. A perfect trio.

As I downed the last of my red wine, Blake equally loosened, turned to me to ask, ‘Wait, when did you last have a period?’ My eyes widened with pause. Blake laughingly took the bottle from my hands and happily saw it to its end before we snuggled in with Henry for the night, the stars painted overhead across the darkest of dark.

The next day, a pregnancy test confirmed what Blake and I already had concluded – him gleefully, me in disbelief. How could this have happened? I literally made a living on helping women plan their families! Against unfavourable odds, somehow life had doggedly taken up residence in my just newly post-partum womb.

At home in Sioux Lookout, the long light of the June day pulled across the lake and saturated the view of our floor-to-ceiling windows. At the kitchen table, I sat alone. In my hands, I held a glossy, black and white image that so blatantly and indisputably proved what I had hoped had been a giant misunderstanding with my body. I wept, heartbroken. So swiftly was time falling away from me with my baby. From a rapid return to work to now the news I would soon have another all-encompassing being demanding my attention away from Henry’s perfect curls. I was devastated.

Of course, I now cannot imagine our lives without our shy, yet spunky, rough-and-tumble, red-headed firecracker. But truth be told, it took many months for me to adjust to our two-baby household. For Henry, however, at sixteen months old, he instantly gained a. life-long partner in crime. For his entire living memory, he will never know life without his sister by his side, for better or worse.

In late 2020, the pandemic had hit just as Alice had began her transition from her comfortable and deeply-loved home daycare to school. After barely attending more than seemingly a handful of consecutive days of junior kindergarten at Sacred Heart School in Sioux Lookout the provincially-mandated ‘virtual school’ was ordered. Not one to stick to the lesson plan, Alice and Henry spent the majority of their COVID days together playing and adventuring outside with Blake. With an overarching cautious approach, we shied away from play-dates in those early days and soon Alice and Henry became more inseparable than they had ever been. Their fights were fierce, but their love fiercer.

This fall, we landed in Kimberley mere days before Alice’s first day of in-person Kindergarten at her new school. I was beyond terrified, anxious and worried we had forced Alice and Henry into a situation that would be somehow irreparably harmful. It was a massive transition in more ways than one.

Henry sailed through those first weeks without a backwards glance, but the new school, the loud and chaotic change of environment and daily separation from home was a challenge for Alice. At our first parent-teacher interview, Alice’s soft-spoken, quintessentially gentle Kindergarten leader informed us that Alice was having difficulty making new friends. At recess, she would immediately seek out Henry and tail him for the duration of their time outside. They could not be separated.

Back at home, feeling my way through the dark, I stepped carefully down the wooden staircase, the boards creaking in protest. As I had predicted, Henry’s door had been flung open. All was still as I went to investigate. Poking my head inside Henry’s doorframe, I made out a small duvet-covered mound encompassing only the most upper corner of his double bed. Peering closer, the details of the singular lump came into focus. Softly, their breaths rose and fell, their bodies entangled into one. My two babies, cocooned together, enveloped in their beloved lambskin fleeces. Henry’s arm loosely flung over Alice’s side, their bodies mirroring each other’s, spooned together into one. My whole world. Right there in front of me.

As Omicron cases surge, schools and gyms are shuttered (again), visits with friends and family erased from the family calendar, there is very little good that I can say at this time that has come from this pandemic. I’m tired, I’m beyond irritated and yet again, I feel the grief and longing for normalcy permeating my thoughts. Truthfully, I’m finding it difficult to stay present and to sit with our collective suffering. Yet, the deepness and simplicity of my children’s sibling love has reminded me that all is not lost and the strengthening of their bond has certainly been a silver lining to these past two years. As the ground continues to shift under our feet, I hold this image of my spooning, slumbering children close to my heart. One foot in front of the other, hour by hour, day by day.

So, as we carry on in the midst of yet another wave of COVID cases, I send my solidarity and love to all of you parents and caregivers out there who, each morning, steel yourselves for another day of impossibility. Homeschooling, working from home, wading through the chaos, trying to maintain some semblance of a relationship with your spouse, all while attempting to cling to the last of your lingering sanity, I feel you. We all do. There is no easy way out but only comfort in the collective. Soldier on, my friends.

Less is More

It’s been almost four months of our little Kootenay family adventure, living in Kimberley, BC. Two weeks ago, as a family of four, we put out our first standard bag of garbage for pick up since we moved in at the end of August, and I cannot say how surprised I am!

Over the past four years, we have slowly been making small, but consistent changes in our family to minimize our environmental impact. You may recall a post I wrote back when the kids were 2 and 3 years old on how we had been collectively moving towards eliminating single-use plastics. Since then, we have worked diligently at simply buying less, reducing our consumption of plastics and have largely diverted most waste to compost or recycling.

On our arrival to our new digs in Kimberley, Blake and the kids had chatted about a family goal of one standard garbage bag every three months as our garbage ‘allowance’. The kids were all for it. I was the one who was skeptical. Previously, we had been producing about one garbage bag a month, how could I cut that back to a third!? Frankly, I felt it was an unachievable goal and humphed around the house about it but Blake and the kids remained steadfast. ‘We can do it, Mom!’ they said.

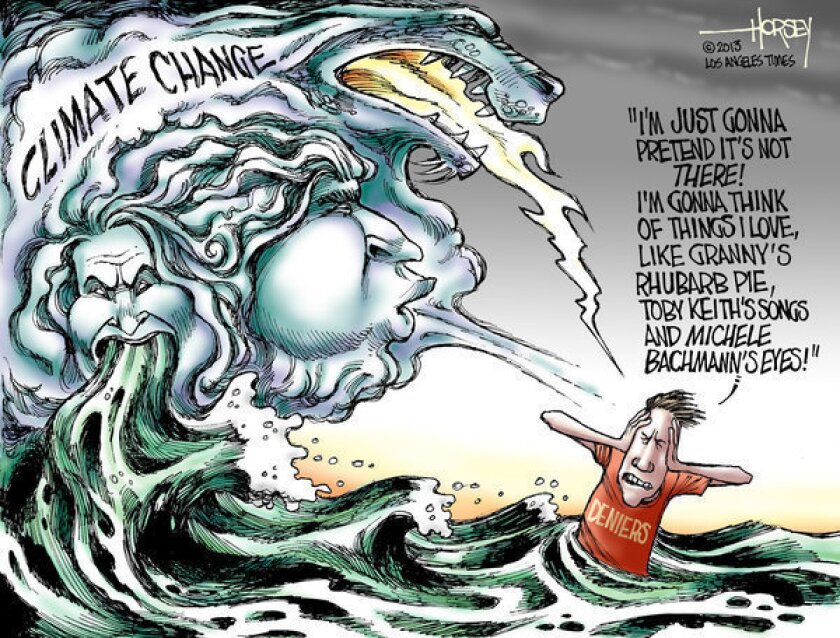

Perhaps it’s because we are deep in the season of frenzied buying for the Holidays, or maybe it’s the fact that every day, I look to our snow-bare local ski hill that usually would have skiers racing down its slopes by now, or maybe it’s in light of recent natural disasters across our province, but I’ve been reflecting much on our relationship with our struggling planet of late.

As a parent, it’s easy to spiral into a negative space when thinking of our children’s and our grandchildren’s futures. Regularly, I see direct consequences of climate change on patients’ health in our family medicine clinic: kids and elders with respiratory illnesses who were forced to spend their summers indoors due to devastating, raging forest fires across British Columbia, youth with sky-rocketing levels of eco-anxiety linked to feelings of hopelessness for their futures, higher rates of depression among adults whose livelihoods, financial and food security are all directly affected by increasing rates of climate disasters and extreme weather events across our country (with Indigenous communities being most gravely affected).

Trust me, I deeply empathize with the urge to metaphorically stick our heads in the sand, to cling to climate change denial, to cover our eyes and pretend all is well and to plod on blissfully unaware.

It’s an effective strategy, one that I use on the regular at home when the kids are being too wild. I pop in my noise-cancelling earbuds and boom, all is seemingly fine! ‘Ignorance is bliss,’ my dad would always say to us growing up. It’s a much easier existence to ignore than to act.

While this blog post may be incongruent with the cheerful holiday music playing overhead or the commercial messaging of ‘Everything’s just fine! Keep on buying!’, I’m truly not trying to squash the joy of the season or be a Scrooge. The point here is also not to point fingers, lay on the guilt or polarize opinions, but to perhaps pump the brakes a bit and reflect on how we all might make small changes this Christmas and to maybe imagine a better way forward for 2022.

The Van Winckles’ Guide to Sustainable Planetary Existance 🙂

Haha, just kidding! Not for a second do I profess to be an expert here or claim to be perfect in any way. I’m not a climate scientist, nor do I feel it is even my place to tell people how to live their lives. You do you.

However, if you’re looking for ways you make some sustainable changes for 2022, here are a few strategies that our family have committed to in reducing our impact on the environment and honestly if we can do it, I know that you can too.

Holiday Bonanza!

Ok, I realize that for some folks, ‘gift giving’ is their love language, but have you ever been present during a Christmas morning when kids are tearing through seemingly endless presents like possessed demon children? At the end of the frenzy, they have no idea what they were actually given or who the gifts were from and you’ve barely had time to register their reactions to their gifts. Worse yet, you haven’t even had a moment to take your first sip of coffee. The kids’ brains are so hyper-stimulated and short-circuited that all they can manage to say is ‘Where are more presents? What else did I get?’ Yikes.

So:

- Simply consider buying and giving less! Yes, I know. Novel idea eh? But seriously, PLEASE FOR THE LOVE OF GOD, BUY LESS FREAKING JUNK!!! Do a secret santa with your families or colleagues and avoid buying novelty items that end up in the dump before New Year’s. I promise you that your children and family will still love you if you focus on the quality rather than quantity of gifts this year. You don’t have to be a full-on Scrooge, I love to give and receive gifts and definitely plan on gifting the kids a select number of special presents. All I’m saying is perhaps when instead of panic-buying this year, just pause and think, will my kids’/partner’s/family member’s/friend’s/co-worker’s holiday experience be seriously affected if I skip the extra three gifts I bought ‘just in case’? Is it possible that you could be over-gifting to compensate for something unrelated or out of guilt? From what I see at work, people young and old are largely suffering from lack of connection and loneliness, especially during the Holidays, feelings that are exacerbated by the pandemic. Could FaceTime or a phone call, a visit or a letter be what is actually needed this year instead of the ten items you just bought on Amazon?

- Consider giving experiences rather than buying stuff just for the sake of buying something. Gift a day at the spa, a gym membership, a cleaning service, a random dinner out in the middle of February… (haha, this MAY or MAY NOT be my own Christmas list – Blake take note! 🙂 )

- Buy used. Instead of maxing out your credit card at Walmart, check out your local Facebook marketplace, thrift store or second-hand kids’ store. We almost exclusively buy all of our kids’ clothes, books and toys second-hand. Avoid the packaging and keep diverting products from the landfill!

- Refuse single-use plastics. I fill the kids’ stockings exclusively with non-plastic gifts. Pencil crayons, second-hand metal Hot Wheels cars, chocolate santas in foil wrap, oranges, etc. Resist going crazy at the Dollar Store and buying plastic junk just for the sake of filling the stocking.

- Reuse decorations, gift wrap, bows, etc. Or better yet, use fabric gift bags that can be pulled out year after year. I recently checked out the local thrift store here in Kimberley and there were loads of gently used Christmas gift bags, gift tags, wrapping paper and tree decorations. You may get a few eye rolls (like Blake does to me!) when I carefully fold up bits of wrapping paper to be re-used next year, but think of how much garbage you will save by simply tucking it away for next year.

- Consider making a donation in someone’s name in lieu of a gift. There are endless non-profit organizations, locally and internationally that would greatly benefit from a financial donation this year.

- Get crafty. I’m no Martha Stewart but instead of buying our kids’ teachers a random mug that they will never use, we make cookies and put the kids to work to create a piece of artwork that I then pair with a well-deserved bottle of wine 🙂

- Buy local. Independent buisnesses have been struggling during this pandemic. Buying locally often reduces the packaging associated with shipping while supporting your local economy.

- Try not to loose your shit about this one, but consider eating less meat products over the holidays. Do we really need to cook a massive turkey and a ham for Christmas dinner? Consider plant-based alternatives or at least just reduce the number of meat-heavy mains over the holidays.

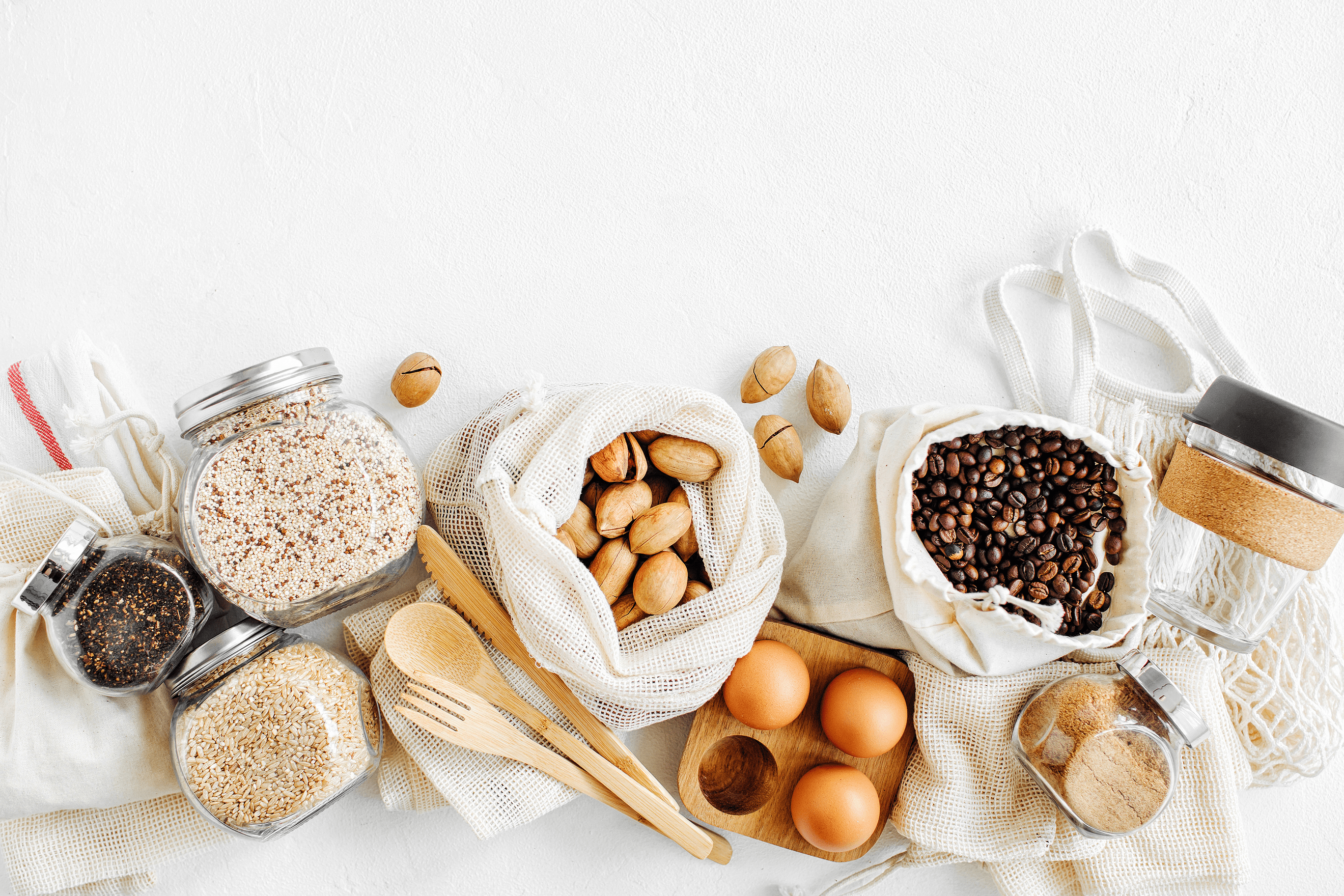

In the Kitchen

Grocery shopping, kids’ lunches, cooking, etc. mostly falls under my portfolio in our home and this is where the majority of our waste reduction has stemmed from. Here are a few areas where we have worked hard these past months to make the most change.

- Refuse plastic bags. Unless you’ve been under a rock for the past few years, it’s now common practice to use resuable bags when shopping. Simply commit to never using a plastic bag. Ever. I mean it! When I forget my resuable bags, you’re damn right that I’m the one begging for a box from the produce guy or just packing out my items to the car arm-full by arum-full. Just refuse. Commit and remember that any plastic bag that you do use, consider it ‘yours’ for the next 400 years. Ok? Great.

- Reduce meat consumption and eat a plant-based diet. Drastically cutting down our meat consuption has made the most impact by far in our family. Without buying animal products, our plastic and styrofoam waste has been reduced to almost zero, not to mention that decreasing our consumption of resource-heavy meat and animal products is an effective strategy to combat climate change. I’m not sayin that everyone must switch to a vegan diet. Our kids still eat meat and I definitely splurge on a burger once or twice a year, but just consider reducing your meat-based meals, even once a week as a start.

- Get naked. I promise you, no one will die if you bring home your produce just as it is. Use reusable produce bags, refuse produce that is wrapped in plastic and please, please stop the insane practice of using plastic produce bags! That plastic bag that you used for the ten minutes to get your broccoli from the store to your fridge will now be in the landfill for freaking years!!!! Gah! 🙂

- Refuse single-use plastics. Yes, at first our kids were grumpy when I stopped buying berries in plastic clam-shells, but now they read me the riot act if I come home from the store with any products wrapped in plastic. I regularly ask at the bread counter for unwrapped loaves to put in resuable bags and I buy our kids’ favourite pepperoni sticks in bulk, directly from the local meat shop wrapped in butcher paper instead of plastic.

- Go big or go home. On a regular basis, we rock the local bulk food store and fill reuseable containers with all of our dry goods: nuts, trail mix, baking supplies, dried fruit, rice, cereals, etc. This has massively reduced our garbage waste by eliminating product packaging all together.

- Kid lunches. Ugh. You know that thing you have to do EVERY. SINGLE. NIGHT?! Truthfully, making kid lunches used to be my pet peeve, but now I actually feel a small amount of pleasure filling little resusable containers with various items – like a bento box for kids! I also make bulk batches of muffins, nut-free energy balls and granola bars to pop into reusable zip locs during the weeks to make their lunches completely waste-free.

- Every day I’m sparklin’! For cleaning products around the kitchen, we buy powdered detergent in a cardboard box for the dishwasher, buy bulk dishsoap or use the local refill station to prevent the need to toss plastic spray bottles.

In the Bathroom

I find the bathroom a low-hanging fruit in terms of going plastic-free and reducing waste. It’s a good place to start because these days, there are so many alternatives to plastic-bottled products. Basically, all of our bathroom waste is paper-based. I use a brown paper bag to line the garbage bin, then every once in a while, I put the whole thing into our woodstove (but could also go in the compost). Here are a few of my faves:

- Shampoo and conditioner bars – I have been using Unwrapped Life bars for years

- Compostable cotton swabs

- Bamboo toothbrushes

- Silk dental floss or bamboo dental floss

- Washable period underwear or a menstrual cup

Kids & Around Town

When looking at kids’ toys, clothes and gear, with a bit of effort, it’s fairly simple to reduce waste. With online gear swaps like Facebook Marketplace, even in small-town Sioux Lookout, I was able to borrow or buy second-hand clothes and gear. We very rarely buy new clothes or toys for the kids. Pre-covid, we essentially used the local thrift store as a toy exchange – each kid would donate a toy to be able to bring a ‘new’ one home which prevented a lot of accumulated stuff. Again, buying pre-loved items not only eliminates excessive packaging but also reduces the carbon footprint of the toy and diverts it from the landfill. For the kids’ birthdays, on the invitation, we politely ask for ‘no gifts please!’ Instead, the kids have received amazing little homemade cards. Not only does it eliminate the massive gift-opening frenzy that I always found to be awkward, but it reduces the stress on families who are under financial pressure. In our experience, as long as there are cupcakes, our kids haven’t even noticed a ‘lack’ of gifts!

Take Home

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for letting me stand on my soap box!

I hope that it may give a few of you pause in the heat of this consumer-crazy season and perhaps inspire you for the New Year ahead.

A few parting notes:

- Progress over perfection. The same mantra that I use for my weekly workouts, is so applicable here (and in most scenarios!) too. The planet doesn’t need you or any of us to be living an envinronmentally-conscious lifestyle perfectly and certainly we are also far from perfect. I still use standard, store-bought deodorant and I definietly still drive to the gym at 6am because I’m too lazy to bike in the cold, dark. Expecting perfection isn’t realistic but just like at the gym, putting in consistent effort to make small changes over time leads to massive results.

- Low-waste living is for the priviledged. Agreed. When you don’t have to worry how you’ll feed your kids their next meal or whether a comment to your partner gone wrong could land you in the ER, you sure as hell don’t have capacity to be considering your impact on the planet. Our family is certainly privildged in this way, and I do acknowledge this. However, if you and your family are also similarly privildeged, consider engaging in a discussion with your partner, your kids, etc. What could your family do differently for 2022 for the health of our planet, and subsequently for the health of your community and communities worldwide. You’ll be surprised, the kids are usually the ones who are most gung-ho!